Posted on Thursday, September 19, 2019

I'm extremely pleased to present the third Studydrawing.com artist interview. This time with my very good friend, Grigor Eftimov. I first met Grigor during my first stint at the School of Representational Art, in Chicago, in 2001. Grigor and I instantly hated each other and were very competitive. I left Chicago after two years and returned in 2007 to finish the final two years at SORA. By that time, Grigor had graduated and was one of my teachers. The second time around, I had great respect for Grigor and his teaching, and learned a tremendous amount from him. We became good friends and from mid-2012 to 2016 we shared the studio space together that would become Atelier Eftimov.

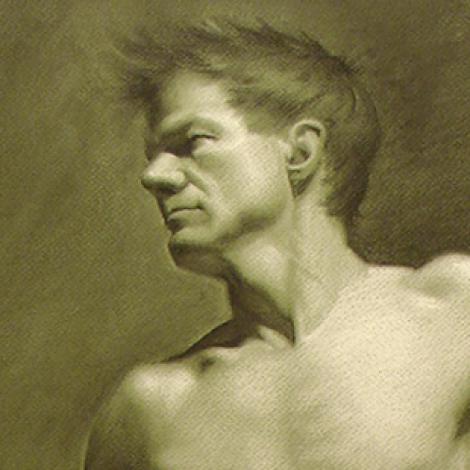

I truly believe Grigor is a world-class artist and among the people alive today with the most and deepest experience with all aspects of drawing and teaching drawing. Grigor has had intense and deep experience as a teacher, won national awards for his caricature work, worked as a professional story-board artist for years, and produces stunning original artwork. In this interview, we go deep into how his background has informed both his art and his teaching and cover ideas and concepts critically important to art and drawing.

Ben: Thanks for chatting with me, Grigor. Could you please describe your background as an artist and how it all started?

Grigor: I was born in Macedonia, formerly part of the Republic of Yugoslavia. I came with my family to the United States when I was four years old. Before that, when we were migrating to the U.S., one of the earliest things I remember was taking a train with my family. I remember being in the train station and amazed by the toy train models. I told my father that they were so cool and I really wanted one. When I got into school and I was told to draw something I remembered from the summer, I was still obsessed with the trains, so I drew trains. So that was the first thing I remember drawing.

We ended up moving around a lot. My father was not a person that could stay in one place for long. He was the type of person that was always willing to gamble that things would be better somewhere else. So we lived in North Carolina, then moved to New Jersey when I was in second grade. Then we moved to New Hampshire for half a year, then went back to Europe. My father did not know where he wanted to settle and did not want to go back to Macedonia, so we visited Frankfurt Germany for a couple of weeks. Then we went to Prague for another couple weeks and ended up back in Macedonia for about a year. Then the Balkan war broke out, which scared my father, so we moved again and this time to New Zealand for several months, then to Australia for a year. Then we finally ended up back in the U.S., in Illinois, when I was a Junior in high school. So it was a full circle around the world. I kept doing the art and drawing the whole time.

My first experience with life drawing was in Australia when I was fifteen. The school system there was much more similar to American colleges and universities. It was a lot more rigorous and classes would be twice a week for two hours instead of every day, including the art classes. I didn’t like the art class at first, but I appreciated the opportunities it provided. With the class I went to an art museum for the first time with a trip to the Art Gallery of New South Wales in Sydney, where I saw a Rubens exhibit for the first time. At the time I was heavily into comics, and drawing comics, and all I wanted to do was comics. When I saw the Rubens exhibit my brain exploded and I saw that there was way more out there in art than just comics.

"When I saw the Rubens exhibit my brain exploded..."

Eventually part of the class was doing some life drawing. They hired a model. I was the youngest in the class so I had to get a formal release from my parents. On the first day, there were maybe ten students in the class. They shut the blinds and locked the door. This was the first time I had ever seen a live nude model, and as I was so young, it was quite embarrassing. My buddy and I were in the back of the room joking around, and the model comes in and drops her robe. I was very shy and got really embarrassed and started laughing uncontrollably and could not stop. So I had to leave and compose myself. When I came back, I just focused on drawing and doing drawings like I had learned to do copies of Old Master drawings. After I calmed down, I took to it right away. It was surreal watching my brain adjust and it went from a naked person in front of me to just drawing and rendering a figure.

Soon after that, we returned to the U.S. and to Illinois, and I went to Morton East High School in Cicero. I met a good buddy there. It was hard to find peers that had similar interests. But my friend was in my art class, and at first, we were very competitive, but then became good friends. He went off to make video games. He really motivated and challenged me. Then I moved again to the suburbs and to Lake Park, which was a bad experience. At that point, I gave up on school. I actually didn’t graduate from High School as all the moving got to me. I had a bad relationship with the art teacher there. I don’t know what it was, or if she was intimidated by me. I told her “I’m not feeling your class. I don’t need your class. I’m going to art school. And that’s that.” And then I went to the American Academy.

Ben: Tell me about your experience at the American Academy.

Grigor: I didn’t go right away. I took some time off and started at the beginning of 1997. It was supposed to take only two years, but it took three and a half years. I took one semester at first, because I could only afford one semester, because I had to pay in cash. Then I took a year off to work with my father doing asbestos abatement. After that I was able to pay for another year and then I started a job doing caricature drawing which allowed me to continue. During that time I signed up for the Electronic Design class. I didn’t think much of that program so I switched to Illustration. I didn’t think much of that program either, so I switched back to Life Drawing and stuck with that.

Ben: Tell me about how you found The School of Representational Art (SORA) and got started there.

Grigor: The way it happened was I took another year off, after the Academy, and worked a cargo delivery job in the winter and did caricature drawing at Six Flags over the summer. I had some money saved up and I was very seriously considering going to study at an Atelier in Florence. Then reality kicked in and I realized how much it would cost. I didn’t have a patron or benefactor and my parents would not be able to help me, so I had to find something else. A former student from the American Academy I knew, named Chela, showed me a magazine article about SORA. So I followed up, set up an interview and visited the School, and I knew I wanted to study there.

I started studying there at the beginning of 2001, and finished the student program after four and a half years. In my third year, I started teaching the weekend classes. After that, I started doing Alla Prima painting workshops. Over the summers I taught the mini-Atelier program (a compressed drawing/painting course) After I graduated I became faculty. I would come in twice a month, along with the other teachers: Steve Ohlrich, Bruno Surdo, and Michael Chelich. I did that until the fall of 2013 when I stopped teaching at SORA and founded Atelier Eftimov.

Ben: How many students left SORA and came to study with you?

Grigor: Six of them. Word got out and people joined me. It forced me to turn my studio space into a place I can have students do Atelier work during daytime, evening, weekend classes, and workshops. I’ve been running it ever since.

Ben: So you’ve been teaching drawing and painting for 12 years now. What have you learned about drawing and painting from teaching this long?

Grigor: I’ve learned that drawing is hard. That’s the bottom line. Drawing is the hardest thing in art. If you can draw, then you can paint, then you can be an illustrator, then you can do comics, you can do anything. If you can’t draw, you alienate yourself from so many things in art.

To me, drawing is more about observing and less about the actual act of drawing. The act of drawing is the technical aspect. When seeing and the technical part come together, that is when you have a good drawing. So after teaching for a while I’ve seen that people that think they can draw well, really can’t. Until they really start learning how to translate what they are seeing onto paper and making that connection, it’s hard. When you are really in-tune with your drawing, you take ownership of what you are doing, and you don’t think about the act of drawing and just focus on observing. When you are drawing, it should be like breathing. You don’t think about your breathing, normally, unless you focus on it. So when you are drawing well, you’re not thinking about drawing. When you’re connected with what you're doing. It’s a zen experience. When I think about ideas for art, I don’t write them in words, I draw them. I don’t sit there and worry about the act of drawing, being able to draw lets me figure out ideas through drawing. The better I can draw, the easier ideas come out and the better I can articulate ideas.

Another thing is when you are a teacher, your students are like your children. The sense that I mean that is that you are responsible for what they do. If you, as a teacher, don’t take ownership of that, you can pass it off with the excuse that “[this student] is not talented, or not cut out for this type of drawing.” And I think that is nonsense. If you, as a teacher, are going to take credit for the good things your students produce, you’d better take responsibility for the sub-standard work your students produce. So what this has taught me is to take ownership and be responsible for my students.

I make teaching my own ongoing project. Each time I teach, I try and fix or adjust myself to hone-in and be clearer and present the information better. Every student is different and starts from a different place. As a teacher, I don’t want to force each student into a certain mold. At the same time, I want things to come out a certain way and want my students to do good work and good drawing, so each student is a challenge. Some people are easier to reach, some harder. Some people have it easier, some have it harder.

For example, as I mentioned I went through different types of art classes, myself. In high school, I was just the weirdo lost in a sea of people and no one cared. At the Academy, there was a lot of competitiveness and energy, and people got jealous and envious. When I got to SORA, it was a very different vibe. It was much more intimate. There were students of all different ages and abilities. Everyone was working at their own pace and trying to do their best.

Ben: Has the way you teach changed since you started teaching?

Grigor: It’s very similar, but it has changed. As a student, when you’re learning, you take information from various people (other teachers.) And that eventually teaches you to be a teacher, because you see what works for you, and you take it. And from all that I add to it things I was not taught, but figured out and believe in. So, in general, what I teach is still similar to what I learned, but what has changed is manifested in things I emphasize more or less.

I’m very big on getting the impression or capturing the large visual impression. I’m very big on squinting. A lot of times people will run into problems where they get stuck in an area. So, on the first day, I tell them, to the point where it becomes a bit of a joke, to keep squinting. If your drawing sucks, squint. If your color sucks, squint. If your value sucks, squint. Squint for everything. What squinting does is it takes you a step back. It pushes you away from the subject and allows you to see it in a simpler way. With whatever you’re drawing, there will be a lot of information, lots of shapes and patterns and details. The last thing you want to do is get hung up on details. So, at the very beginning of your drawing, the first thing you want to do is squint down and capture the impression. That is the first thing I emphasize. Your impression may not be perfect, but it’s something you need to stick with, from the beginning to the end. I strongly believe that.

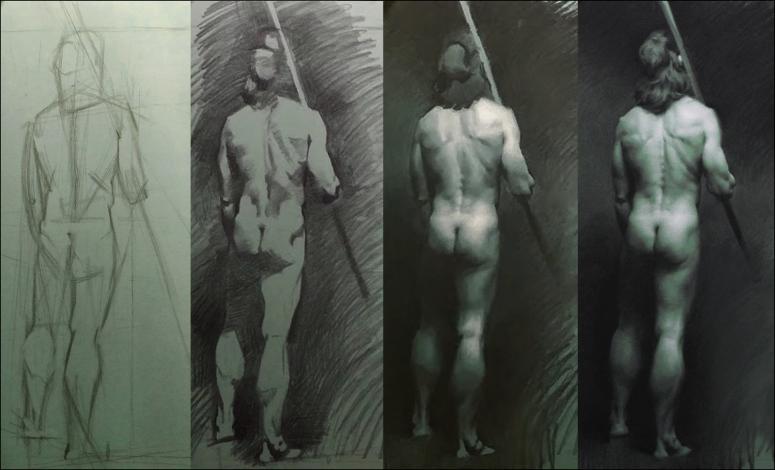

When I was a student, we didn’t do gesture drawing every time we had a model. When I have a model, we do gesture drawing every time. It’s a must and a given for me. To me, how well a student can do gestures or quick sketches, tells me exactly what their level of drawing is. If a drawing takes two hours or sixty hours, it does not really make a difference. Either you can capture in a gesture drawing the feeling and the impression in 30 seconds or a minute or so, or you can’t.

An important thing I think was lacking when I was a student, which I really try to hone in my classes, is I want to make sure students see the connection between the first marks in the first 30 seconds and the last marks after 60 hours. It’s all the same. Because, the thing is, if you had 30 seconds, 30 minutes, or 30 hours, you need to hang on to that immediate basic impression to avoid it looking laborious to people.

Ben: Can you elaborate on what you mean by impression?

Grigor: When it comes to drawing, it’s you as an artist, and an individual, reacting to nature. (Ed: “nature” in this context refers to the subject or object being drawn, or the external world as-is). If it’s a model, every pose has a certain energy. The impression is the energy. You can describe it as very basic visual feelings. I could ask...how does this pose feel to you? Does it feel open? Does it feel closed? Does it feel sad? And if you ask yourself about your reaction to the pose… how do you feel about the pose? Do you like it, do you dislike it? If you like it and it excites you, you should ask yourself, what about it excites you about this pose? You have to find that as an artist, what draws you in, and what your impression is and what the impression is. For example, if the model is standing with all their weight shifted to one side of the body, you need to see that as a whole and focus on that, as a whole, to be able to translate it on to paper.

Ben: How would you say the concept of ‘impression’ relates to the concept of ‘essence’? Because one could interpret the word ‘impression’ as an opinion or judgment of what one is seeing. In contrast, ‘essence’ can be interpreted as something part of what you are looking at, and different from one’s evaluation or opinion.

Grigor: For what I’m trying to get across to students, I think it’s both. It’s how can you say the most (in your drawing), in the least amount of time. A student that has more skill and experience is not going to be in the dark as long. They will get to the point, a lot quicker. Going back to the point I made earlier about how an experienced student will just be drawing, and not thinking about the act of drawing. In contrast, for a beginning student, the process is much more one of exploring and trying to feel out the pose in the dark. So I guide students to start asking themselves about what they see, and reacting to what they see and feel, as a way of staying focused and avoiding getting hung up on details.

Ben: If there is one thing a student could focus on to get the most out of their time and effort applied to improve their drawing, what would that be? You’ve mentioned gestures, is that it?

Grigor: I would say draw with a pen. Have a sketchbook, and using a pen, try to only make the least amount of marks, or only marks that enhance the drawing. Also, draw things or subjects that are going to move or change that you only have a short time to observe. I say this because when you start learning to draw, there is a lot of searching out, and you draw a lot of unnecessary lines. If you restrain yourself this way, you learn to get comfortable with just looking. It takes a lot of focus and observation, and observation about the way you are observing, because you may be observing the wrong thing.

This is why time restraints are vital because if you have too much time you can fall into the trap of thinking “well I can just start with the head and work my way down.” You don’t want to do that as you’ll miss the big picture. So this is why things that are short or 30 seconds or so are important. They force you to use your visual memory and buckle down and get to the point right away. If you learn to do it this way, and you find yourself with more time, you can breathe easier and take your time. So I think, in the beginning, it’s good to put yourself on edge a little bit and not be able to erase and to have to think a few steps ahead, like in chess. I would say doing this helped me the most.

Ben: Do you think a student can and should practice doing gesture drawings on their own? (without a teacher)

Grigor: Yes, but only after they’ve had some instruction. The student should know what a successful gesture is and what feels right. Because you shouldn’t keep practicing something you’re unsure of. You don’t know what you’re practicing. So a student needs some good examples or guidelines to go on. Because everything is built on learning to capture the gesture, and once that’s done you can build upon that into a more refined drawing or painting.