| Title | Image | Page Summary: |

|---|---|---|

| Jombert - A Method for Learning Drawing | ||

| Jombert - Method - Page 1 |

|

The text outlines a method for learning drawing, providing rules and guidelines to master the art quickly. It includes plates of human anatomy as depicted by Raphael and other masters, along with academic figures by Cochin, and studies of antique statues and landscapes. The book is authored by Charles-Antoine Jombert and published in Paris in 1784. |

| Jombert - Method - Page 2 |

|

The preface discusses the proliferation of drawing books and highlights the uniqueness of the author's approach. It references various well-known artists and the importance of providing a more structured guide for drawing, with an emphasis on using excellent engravings from Italian masters. The aim is to offer comprehensive principles to assist learners in mastering the art of drawing. |

| Jombert - Method - Page 3 |

|

The preface discusses the usefulness of the book for those learning to draw, emphasizing the benefit of practice alongside theoretical study. It is intended as a resource in places lacking access to skilled instructors. The book is organized into eight chapters, focusing first on human anatomy and including illustrations to aid understanding. |

| Jombert - Method - Page 4 |

|

The text provides an overview of a book on drawing, highlighting its main focus on the study and understanding of human proportions. It includes instructions on drawing techniques, paper selection, and shading methods, as well as detailing ancient sculpture proportions. The work aims to aid learners by compiling important insights into a single volume. |

| Jombert - Method - Page 5 |

|

The preface explains that the text offers insights from experienced artists who have studied in Italy, discussing both the strengths and weaknesses of notable artworks. It details the approach for young artists to mimic nature through structured study and the importance of techniques like chiaroscuro in art composition. Additionally, it provides guidance on copying designs, including mechanical methods, to aid those less familiar with drawing. |

| Jombert - Method - Page 6 |

|

The preface discusses the inclusion of mathematical instruments and perspectives in the book, drawing from the works of noted mathematician M. sGravefande. Artists have successfully utilized these methods for creating detailed drawings of landscapes and structures. The work is richly supplemented with one hundred plates demonstrating various drawing techniques and aims to be beneficial to its readers. |

| Jombert - Method - Page 7 |

|

The text on the page is a single word 'METHOD,' suggesting the section's focus on artistic methodologies. |

| Jombert - Method - Page 8 |

|

The text introduces a method for learning to draw, highlighting drawing as essential in painting. It discusses portraying the human body's structure and muscle movements accurately to capture different actions. Emphasis is placed on the importance of understanding surfaces and visible forms to enhance artistic representation. |

| Jombert - Method - Page 9 |

|

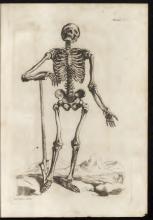

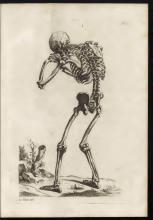

The text discusses the nature of drawing, emphasizing the importance of understanding proportions and the intelligent arrangement of lines to depict reality. Drawing is described as both a mental and practical skill, requiring extensive practice to master. It highlights the significance of anatomy, particularly osteology (study of bones) and myology (study of muscles), to accurately render the human form, the most perfect creation of nature. |

| Jombert - Method - Page 10 |

|

The text discusses the importance of understanding the anatomy of muscles, nerves, and bones for artists. It suggests that rather than performing dissections, artists should study well-illustrated anatomical drawings to learn about posture and movement. Leonardo da Vinci is mentioned regarding the understanding of muscle and nerve interactions. The careful structure of the skeleton is also highlighted for its role in enabling movement and supporting the body. |

| Jombert - Method - Page 11 |

|

The text describes the anatomy of the human body's skeletal structure, focusing on the spine, neck, ribs, and clavicles. It explains the spinal column made of vertebrae, the sternum's role in connecting the ribs, and differentiates between true and false ribs. The clavicles are also mentioned as crossing bones that support the neck area. |

| Jombert - Method - Page 12 |

|

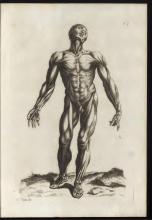

The text elaborates on the skeletal and muscular structures of the human body, particularly focusing on how bones like the sternum and shoulder blades are connected. It describes muscles as structures that enable movement by attaching to bones, receiving sustenance from arteries, and being controlled by nerve impulses. The description highlights the muscles’ various shapes and functions, emphasizing their role in voluntary movements and the changes they cause to the body's form. |

| Jombert - Method - Page 13 |

|

The text discusses the muscles around the neck, chest, and abdomen, explaining their positions and roles. It includes descriptions of the mastoids, deltoids, pectorals, and rectus muscles, among others. The text also explains how these muscles were understood and depicted differently by ancient anatomists. |

| Jombert - Method - Page 14 |

|

The text discusses the origins and insertions of several muscles in the human body, such as the trapezius, serratus, and scapular muscles. It explains how these muscles are visible from different views and their functions, including lifting and lowering the arms. The description includes anatomical terms and may reference anatomical figures or illustrations typically seen in art and anatomy books. |

| Jombert - Method - Page 15 |

|

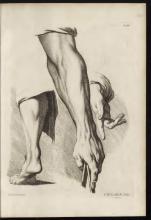

The text discusses the anatomy of muscles, focusing on how they connect and operate within the human body. It explains the muscles related to the spine, chest, arms, and forearms, detailing the origins, attachments, and functions of these muscles. The description includes the bicep, brachialis, and elbow extensor muscles, providing insights into their anatomical structure and roles in movement. |

| Jombert - Method - Page 16 |

|

This text is an anatomical description of the muscles of the forearm focusing on their attachment and function. It explains how muscles such as the supinator and extensors interact with bones like the radius and humerus to facilitate hand movement. The composition and position of muscles influencing thumb and finger movements are also discussed. |

| Jombert - Method - Page 17 |

|

The text discusses anatomical features, focusing on the muscles of the arm, hip, buttock, thigh, and leg. It describes the origins and insertions of these muscles, particularly highlighting muscles like the palmaris, greater trochanter, gluteals, and sartorius. The document aims to educate on muscle structure in relation to art and drawing. |

| Jombert - Method - Page 18 |

|

The text describes the anatomy of the thigh and leg muscles. It details the origins, insertions, and functions of the three-headed muscle in the thigh and the main muscles in the leg, including the anterior tibialis and fibularis. It also discusses the soleus and flexor of the toes muscles on the inner side of the leg. |

| Jombert - Method - Page 19 |

|

The text explains the main movements of the human body, focusing on how these occur at the joints of the bones. It describes the ankle, knee, and hip joints, detailing the nature and limitations of their movements. It emphasizes that any extreme movements are unnatural, providing anatomical insight into how bones and joints interact to create motion. |

| Jombert - Method - Page 20 |

|

The text discusses the rules and possibilities of contorting different parts of the human body, emphasizing the head, neck, spine, loins, shoulder, and arm joints. It explains how the hand can perform moderate movements aided by the forearm bones, and notes that non-natural movements are frowned upon in art. It describes how certain body sections, like from the clavicles to the stomach, remain largely unchanged due to fixed muscles and bones. |

| Jombert - Method - Page 21 |

|

The text explains how the positioning of the body affects the appearance and order of the muscles and skin. When the body bends, muscles can be concealed or exposed, changing their natural form and order. These concepts help artists understand muscle structure for more accurate depiction in art. |

| Jombert - Method - Page 22 |

|

The text discusses the proportions of the human body in art, emphasizing the importance of correct limb size and length. It highlights how experienced individuals have documented rules for these proportions, aiding young artists in their learning process and preventing them from having to do extensive personal research. The text also references renowned antique sculptures that can serve as models for understanding human proportions. |

| Jombert - Method - Page 23 |

|

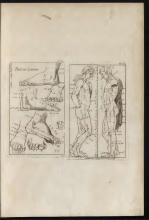

This page discusses Vitruvius's observations on human body proportions and their significance in architecture. Vitruvius notes that a person's extended arms and height are equal, demonstrating the body's symmetry. The text further describes dividing the body into sections for measurement, emphasizing proportions from the head to the feet, and dividing the face into three parts. |

| Jombert - Method - Page 24 |

|

The text discusses Albert Durer's extensive exploration of human proportions, specifically highlighting his guidance on using varying numbers of head lengths to determine figure height. Durer's approach entails manipulating proportions, particularly the head, to achieve figures of different head counts while maintaining a consistent line-based height. The text also details the proportional relationships of the body's main sections: the trunk, thigh, and leg, emphasizing that natural design supports the upper body. |

| Jombert - Method - Page 25 |

|

The text describes a method for drawing figures with different proportions based on the number of "heads" used as a unit of measurement. It explains how to divide the height of a figure into different parts to achieve various sizes and proportions. Specific instructions are given for figures comprising seven, eight, nine, and ten heads, with guidance from Albert Durer on handling hair and face proportions. |

| Jombert - Method - Page 26 |

|

This section describes Albert Durer's method for measuring the proportions of young children. The text outlines a detailed division of the body's height into parts, specifying how each section corresponds to parts like the head, neck, and limbs. These measurements are meant to help artists accurately draw children's figures in proportion. |

| Jombert - Method - Page 27 |

|

The text explains a method by Guillaume Philander, attributed to Varro, for dividing the human figure into nine parts to understand proportions. The proportions detail the head, face, and other parts of the body, using fractions of these nine parts. It notes inaccuracies in the historical portrayal of children's proportions compared to adults. |

| Jombert - Method - Page 28 |

|

The text discusses the proportions of the human body in drawing, referencing antique statues like Laocoön and Venus, noting that hands are slightly longer than the face for gracefulness. It outlines methods by Pomponius Gauricus, who suggests various numbers of face lengths in body height, advocating nine as the most accepted among artists. Detailed instructions are given for dividing the body into these proportions. |

| Jombert - Method - Page 29 |

|

The text describes proportions of the human body using a concept of 'faces' as measurement units. It explains how various parts of the body, such as the thigh, knee, leg, and arms, correspond to these units. The section attributed to Daniel Barbaro elaborates on perfect human proportions, expanding the measurement system to ten faces and explains further divisions, particularly concerning the head. |

| Jombert - Method - Page 30 |

|

The page discusses the proportions of the human body in art, breaking down distances between various body parts such as the eyes, mouth, chin, and more. It explains that the length of extended arms matches the total height of the figure and provides detailed measurements for each section. The text highlights the complexity of these measurements and their alignment with established proportions. |

| Jombert - Method - Page 31 |

|

The text provides an overview of the proportions of the human figure as described by the Italian author Jean-Paul Lomazzo, who was influenced by Albert Durer's guidelines. It outlines how the body is divided into ten parts for both the vertical aspect and when the arms are extended. Lomazzo's divisions help in understanding the structure and aesthetics of the human figure in art. |

| Jombert - Method - Page 32 |

|

The text discusses the proportions of human figures, referencing the methods of Jean-Paul Lomasle as clarified by a French author. It explains how traditional figures are divided into units called 'faces,' extending from head to toe. The methods are aligned with classical standards set by Vitruvius and streamlined to help beginners understand proportion more easily. |

| Jombert - Method - Page 33 |

|

The text explains proportions and measurements of the human body in relation to drawing. It describes specific body parts and the concept of measuring using "faces" and "noses" as units. The passage emphasizes maintaining accurate proportions when depicting figures, noting that some standard measurements may seem exaggerated, like the size of the foot. |

| Jombert - Method - Page 34 |

|

The text discusses the proportions of the human body, as reported by Felibien, saying both men and women are eight heads or ten faces high. It describes divisions of the body from the head to the feet and emphasizes that human proportions align with those described by Vitruvius, marking the spread of arms being equal to one's height. This general understanding of proportions continues to be relevant today. |

| Jombert - Method - Page 35 |

|

The text discusses the correct proportions of the human figure, explaining how the measurement concept of 'eight heads' is applied from the top of the head to the feet. It details dividing the head into four parts for facial measurements, relating lengths of nose, eyes, and mouth positions. Additionally, the text describes how the arm's length is measured in relation to the head, providing specific points of reference like the shoulder and wrist. |

| Jombert - Method - Page 36 |

|

The text discusses the proportions of body parts for drawing, focusing on shoulders, arms, hands, thighs, legs, feet, and fingers. It provides detailed measurements, comparing them to facial features like noses and heads for reference. The text also notes that these proportions are not strict rules and can vary depending on the desired depiction of figures. |

| Jombert - Method - Page 37 |

|

The text provides guidance for young artists on the general aesthetics of different parts of the human body. It includes advice on how to shape the forehead, eyes, nose, mouth, chest, and arms for ideal beauty, referencing techniques by renowned painters. The guidelines emphasize proportions, with specific measures and observations about gender differences. |

| Jombert - Method - Page 38 |

|

The text discusses the artistic representation of human anatomy, emphasizing how men and women’s features should be depicted differently for aesthetic reasons. It highlights the importance of drawing techniques, grace, and elegance, suggesting the study of great masters like Michelangelo and Raphael for inspiration. The passage also speaks to the accomplishments of French artists, who rival their Italian counterparts in painting skills. |

| Jombert - Method - Page 39 |

|

The text discusses the French School of painting and emphasizes the need for specific drawing techniques. It warns against having outer contours meet like balusters and advises on how outer and inner contours should flow. The text also references du Frenoy's idea of contours resembling flames and stresses that muscles should be well integrated based on anatomical knowledge. |

| Jombert - Method - Page 40 |

|

The text discusses the principles of drawing, emphasizing harmony between parts and the whole. It provides guidance on using proportions in human figures, advising beginners to observe proportions by eye rather than relying solely on measurements. It also highlights differences between proportions of men and women, noting specific variations in anatomy. |

| Jombert - Method - Page 41 |

|

The text discusses the differences in proportions between male and female figures, noting characteristics like the narrower chest and thicker thighs of females. It explains how a child's body proportions change as they age. The distinction between a hero and a common man is also outlined, with heroes having idealized features. The text concludes by referencing famous ancient statues that exemplify these proportional differences. |

| Jombert - Method - Page 42 |

|

The text discusses the essential qualities and practices needed to succeed in the art of drawing. Emphasizing natural talent and dedication, it highlights the importance of these elements over mere effort, explaining how mediocre painters often fail due to their lack of innate skill or commitment. Predispositions and recognition of innate talent are crucial for achieving mastery in art. |

| Jombert - Method - Page 43 |

|

The text discusses the natural human inclination towards drawing, expressed through a desire to imitate natural forms and a profound enjoyment found in sketching. It mentions that a passion for drawing can arise from observing painters and highlights key indicators of aptitude, such as a keen interest and the ability to sketch boldly. The text emphasizes the importance of a lively spirit and audacity in excelling at drawing. |

| Jombert - Method - Page 44 |

|

This passage discusses the traits necessary for success in drawing, emphasizing that effort alone cannot surpass mediocrity without innate talent. A love for one's creations is crucial, but it must not blind one to progress. It advises starting the practice of drawing at a young age to avoid discouragement from early imperfections, as drawing requires a long and dedicated period of study to achieve excellence. |

| Jombert - Method - Page 45 |

|

The text discusses the importance of starting to learn drawing at a young age due to the advantages of youthful vigor and creativity. It explains that there is no specific age to begin, as development varies based on individual genius and predisposition. For those intending to become painters, it is vital to identify their inclination toward art early on. |

| Jombert - Method - Page 46 |

|

The text discusses the importance of cultivating imagination, memory, and a positive disposition in students learning to draw, starting as early as ages ten or twelve. It emphasizes the necessity of practicing by imitating body parts and advises against over-reliance on engraving techniques for shading. The goal is to express ideas with simplicity and avoid overburdening the mind, maintaining creativity and avoiding a mechanical approach to drawing. |

| Jombert - Method - Page 47 |

|

This section discusses the importance of consistent practice and balancing enjoyment with effort in learning art. It emphasizes the need to allocate proper time to each study and vary activities to prevent boredom. The text also highlights the adaptability of young minds in acquiring multiple disciplines simultaneously. |

| Jombert - Method - Page 48 |

|

The text discusses the process of teaching students to draw by initially copying parts of the face and eventually moving to entire figures. The emphasis is on using high-quality originals, and the text advises gradually introducing more complex subjects to avoid overwhelming students. There's a focus on the importance of students developing their own drawing ideas after mastering proportions by copying. |

| Jombert - Method - Page 49 |

|

The text advises teachers on encouraging students to develop their drawing skills through inspiration and selective feedback, emphasizing both copying originals and fostering creativity. It stresses the importance of balancing praise and criticism to maintain motivation and enhance learning. The significance of finishing their drawings and the impact of teaching methods on a student's unique artistic development are discussed. |

| Jombert - Method - Page 50 |

|

The text advises artists, especially young ones, to carefully finish features like heads, hands, and feet in their drawings, emphasizing the importance of attention to detail. It warns against settling for superficial sketches, which often allure with a false brilliance but lack depth. The author suggests a profound understanding and observation of natural beauty to avoid mediocrity and ignorance in artistic endeavors. |

| Jombert - Method - Page 51 |

|

The text advises artists to balance spontaneity and refinement by completing projects extensively to correct bad habits. Students are guided to practice with increasingly complex drawings, focusing initially on nudes before attempting group compositions. Teachers should allow creative attempts only when students are proficient in copying, to avoid wasted effort. |

| Jombert - Method - Page 52 |

|

The text emphasizes the importance of using renowned artists' works as models and discourages mechanical copying methods in drawing education. It recommends a long study to master drawing accurately and suggests starting with simple plaster models before moving to complete figures. The text highlights understanding shadows and light effects as essential for perfecting figurative drawing. |

| Jombert - Method - Page 53 |

|

The text provides guidance on improving drawing skills through memorization and comparison practices without relying on original models. These practices enhance attention to detail and assist in retaining artistic concepts. It also discusses the advantages of observing nature under different lighting conditions to improve drawing skills. |

| Jombert - Method - Page 54 |

|

M. de Piles suggests a method for learning to draw by first drawing from a model, then trying to redraw it without further reference, while emphasizing the importance of understanding anatomy. The text highlights that becoming skilled in drawing requires more than just copying great works; one must strive to match the masters by gaining a deep understanding of nature. Bernard du Puy du Grez describes a straightforward technique of using slate and chalk to practice drawing. |

| Jombert - Method - Page 55 |

|

The text provides advice on improving drawing skills, emphasizing the importance of practice and observation. By erasing initial flawed attempts and learning from models such as drawings and plaster casts, aspiring artists can gradually develop their techniques. Studying nature is highlighted as crucial for mastering the different movements in human anatomy. |

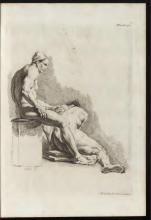

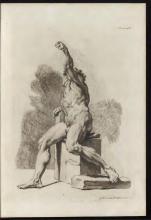

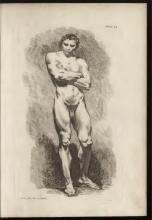

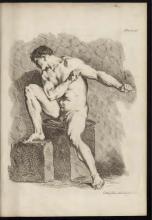

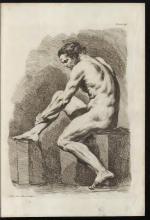

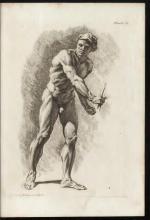

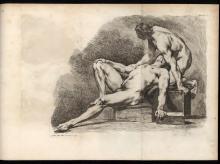

| Jombert - Method - Page 56 |

|

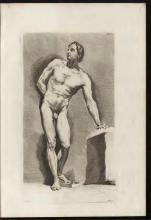

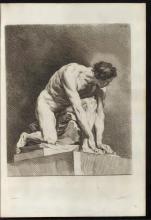

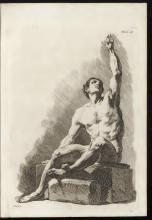

The text discusses the importance of practice drawing from live models, emphasizing the necessity of capturing the natural posture and muscle movements. It advises artists to focus on observing and reproducing nature accurately rather than relying on memory. The passage highlights the value of studying 'Académies', artworks done from live models, for developing one's drawing skills. |

| Jombert - Method - Page 57 |

|

The text advises beginning artists on how to sketch by suggesting they lightly draw a figure without strictly adhering to initial lines, noting changes nature presents. It warns against altering defects found in nature when drawing from a model, as this can lead to a stylized approach and hinder progress. Accurate imitation of the model, including precise color tones, is emphasized to ensure true representation of nature. |

| Jombert - Method - Page 58 |

|

The text emphasizes the importance of anatomy in drawing, particularly when starting to work from nature. It advises artists to mark muscles gently to maintain a balanced depiction of light and shadow. The author warns against overemphasizing anatomical details, as done by some, like Michelangelo, which can result in lifeless figures, instead of realistic ones. |

| Jombert - Method - Page 59 |

|

The text discusses the misunderstanding people had about human anatomy and emphasizes the importance of understanding skin and muscle structure in drawing. It advocates the study of anatomy and drawing from life models to enhance the accuracy and beauty of artistic representations. Additionally, it suggests that artists should not imitate nature slavishly but should select and refine elements to create compositions of great beauty. |

| Jombert - Method - Page 60 |

|

The text discusses the importance of selecting and enhancing the most beautiful aspects of nature while correcting its imperfections to create a well-composed figure. It highlights that beauty is distributed unevenly in nature and effective drawing involves supplementing where nature falls short. The text advises young artists to practice making compositions and softening their technique while also learning from books. |

| Jombert - Method - Page 61 |

|

The text discusses different methods of drawing, focusing on three primary techniques: using pencil, wash, and pen. It explains the types of paper suitable for drawing, including white, colored, and mid-tone papers like gray, blue, and bistre. The text also describes how mid-tone paper can save work with a pencil by serving as a natural base for shading. |

| Jombert - Method - Page 62 |

|

The text discusses methods of drawing and the use of different types of paper and materials. It advises beginners to start drawing on white paper with crayons before moving to tinted paper. The qualities of suitable drawing paper are highlighted, emphasizing strength and even grain. For pen drawings, smoothness and non-absorbency are crucial, while for wash techniques, the paper must be strong and thick to ensure even tones. |

| Jombert - Method - Page 63 |

|

The text discusses the preparation and use of drawing materials such as red chalk and charcoal. It explains how pencils are convenient for beginners due to their ease of erasure. The text emphasizes starting with light sketches and gradually building up the drawing with firmer materials. |

| Jombert - Method - Page 64 |

|

The text provides guidance on making drawings, emphasizing the use of breadcrumbs for erasing incorrectly drawn lines and the importance of using quality pencils. Sketching is described as the initial phase of drawing, where light lines are used to outline a general idea. The concept is likened to the Italian term 'Schizzare,' which refers to preliminary trials likened to color splattering. |

| Jombert - Method - Page 65 |

|

The text explains the importance of sketching lightly before completing a painting to ensure proper proportions and achieve an effective composition. It describes how to create and adjust sketches using soft charcoal and outlines how to progressively practice drawing by copying finished works. The importance of consistent practice is emphasized to gain skill and eventually draw from good paintings. |

| Jombert - Method - Page 66 |

|

The text provides guidance on developing drawing skills with accuracy. It suggests setting goals to train the eye and hand, using comparative methods for judging sizes, and considering mental grids for better accuracy when copying. The focus is on training without over-relying on tools like a compass. |

| Jombert - Method - Page 67 |

|

The text discusses the importance of accurately replicating a model to aid beginners in art. It emphasizes developing ease of execution through practice and perseverance. The author suggests that beginners should start with drawing natural objects or simple artworks to lay a foundation for more complex studies. |

| Jombert - Method - Page 68 |

|

The text discusses the advice that artists should begin by drawing heads, feet, and hands to master proportions and details as these areas are more challenging and require precision. This focus on challenging areas aids in skill development when transitioning to other subjects. Additionally, it highlights the benefits of drawing larger to achieve more freedom and correct proportions in style. |

| Jombert - Method - Page 69 |

|

The text discusses techniques for drawing and shading, emphasizing practicing drawing on larger scales for versatility. It describes three shading techniques: hashing, grainating, and stomping, each offering different textures and depth to the drawing. Understanding these methods can help artists create more dynamic and realistic artworks. |

| Jombert - Method - Page 70 |

|

The text discusses techniques for shading in drawing using pencils and a tool called a stump, made from rolled paper or chamois skin. It explains the method of hatching, where strokes overlap in different directions for shading effects, cautioning against intersecting lines too rigidly. Additionally, it advises on getting accustomed to easily hatching in all directions for effective progress in drawing. |

| Jombert - Method - Page 71 |

|

The text explains a drawing technique that emphasizes minimal sharpening of pencils for effective sketch lines and details. It discusses methods for shading using thick and textured lines by comparing the work with an original to ensure accuracy. Additionally, it stresses using textures judiciously and introduces techniques like cross-hatching to avoid overly soft appearance in drawings. |

| Jombert - Method - Page 72 |

|

The text discusses techniques for creating shadows and half-tones in drawing, emphasizing the importance of balance between bold and soft touches. It advises against overly thin and parallel shadow lines, warning against drawing too round or too angular shapes, which go against good taste. The third method described is shading by softening, using a shading tool to create gentle transitions, especially on white paper. |

| Jombert - Method - Page 73 |

|

The text describes techniques for shading and drawing with pencils, particularly focusing on the use of sanguine (reddish-brown chalk) and black chalk on paper. It covers methods for maintaining highlights and adding depth, using various shading tools crafted from paper or cloth. These methods are highlighted as effective for learning to draw the human figure. |

| Jombert - Method - Page 74 |

|

The text describes techniques for enhancing and preserving drawings, particularly those made with sanguine (red chalk). It discusses the origins of the word 'estompe' and its utility, and provides methods to protect drawings from damage. There's also a note on Jean-Baptiste Loriot's discovery of a process to fix pastels and pencil drawings. |

| Jombert - Method - Page 75 |

|

The text provides a method for creating counter-proofs from drawings using a specific moistening and pressing technique, ensuring the drawing's integrity and quality on different types of paper. It discusses the strengths of red chalk in producing clear counter-proof prints and the challenges with using stone black and pencil. The importance of practicing on toned paper, especially for academic purposes, is highlighted for mastering drawing skills. |

| Jombert - Method - Page 76 |

|

The text discusses techniques in drawing with a focus on using colored paper and wash drawing methods. Drawing on colored paper should involve blending black and white smoothly, allowing the paper color to contribute to the artwork, especially in areas where bones are seen under the skin. It distinguishes between two drawing methods: a light and less detailed style versus a more heavily worked style, suggesting the former is preferred. Additionally, it describes wash drawing, a technique using water and pigments to create strong shadows, commonly using Chinese ink or bistre. |

| Jombert - Method - Page 77 |

|

This section discusses various coloring materials and techniques in drawing, such as the use of indigo, sanguine, and Chinese ink. It explains the wash method for creating shadows, emphasizing the importance of diluting ink to control intensity and using clean water for adjustments. The passage highlights how these techniques differ in speed and thoroughness depending on the desired outcome—a quick sketch or a refined drawing. |

| Jombert - Method - Page 78 |

|

The text explains a drawing technique where layers are gently overlaid to soften edges, suitable for sketching landscapes and refining brush skills. It discusses the use of wash drawing on thick paper to prevent color bleeding and enhance smooth application. The process includes tracing designs with ink and applying successive layers of wash with a damp brush for depth. |

| Jombert - Method - Page 79 |

|

The text discusses methods for enhancing light areas in drawings on tinted paper using various pigments like Spanish white and white lead. It explains why painters mix bistre with Chinese ink to create softer tones and outlines techniques for ensuring the blackstone used in drawings adheres well to the paper. The methods aim to create a softer appearance and ensure durability of the artwork. |

| Jombert - Method - Page 80 |

|

The text discusses techniques for drawing, including the use of various tools and shading techniques such as washes with Chinese ink, bistre, and sanguine. It advises different methods for creating outlines and shading, tailored for more experienced artists versus beginners. The document also mentions specific pigments and suggests consulting other authors for more specialized topics in drawing related to fortifications. |

| Jombert - Method - Page 81 |

|

The text discusses the use of pens in drawing, particularly emphasizing copying engravings and prints to learn the craft. It suggests using crow or goose quills due to their firmness and suitability for precise lines. The text also notes a historical context where pen drawing was used as preparation for engraving, which is now considered outdated. |

| Jombert - Method - Page 82 |

|

The text discusses the limitations of using swan feathers for drawing broad strokes and notes that few drawings are made entirely with a pen. It highlights the superior knowledge and skill of Ancient Greek artists, suggesting that modern sculptors have not quite reached the same level of expertise. The Greek sculptor Polyclitus is mentioned for his dedication to finding the best models for creating well-proportioned statues. |

| Jombert - Method - Page 83 |

|

The text discusses the idealization of ancient statues as models for beauty and proportion, which served as guides for artists. It highlights several renowned sculptures like the Laocoön group and Medici Venus, emphasizing their remarkable portrayal of character, strength, and grace. The passage suggests using these statues to inspire confidence in art students learning about proportions. |

| Jombert - Method - Page 84 |

|

The text discusses the proportions and merits of the Farnese Hercules, a classical statue, emphasizing its role as an exemplary model for artists. The statue represents an idealized human form with divine strength, though its muscles are considered somewhat exaggerated. The notes include a historical context, with the original work by Jean-Baptiste Corneille for the Royal Academy. |

| Jombert - Method - Page 85 |

|

The text discusses the representation of extraordinary figures like Hercules, pointing out that such portrayals often emphasize muscular excess beyond natural form. It advises studying such figures for their anatomical details but warns against imitating their style without understanding. French painters once trained under these models, but this led to mannered art that was less truthful than nature's realistic representation. |

| Jombert - Method - Page 86 |

|

The text discusses the importance of merging truth and beauty in art, emphasizing caution in the use of the famed Farnese Hercules statue. It advises beginners to study it for its clear musculature but recommends moving beyond it to understand nature's truth. The statue, once restored by Guillaume de la Porte, was later validated by Michelangelo, who preferred its modern legs to ancient ones. |

| Jombert - Method - Page 87 |

|

The text describes how figures in the book are divided into sections for measurement. It talks about two statues, Hercules Commodus and Medici Venus, in terms of their artistry and measurements. Hercules Commodus is praised for its proportions, while the Medici Venus is highlighted for its beauty and perfection. |

| Jombert - Method - Page 88 |

|

The text discusses the exceptional quality and beauty of certain sculptures, particularly the Venus de Medici. It compares it to other works like the Andromeda by Puget, noting differences in their aesthetic styles and characteristics. Despite the perfection of ancient sculptures, there are contemporary ways to create beauty, although interpretations and restorations may affect the perception of these art forms. |

| Jombert - Method - Page 89 |

|

The text describes detailed observations and measurements of various famous sculptures, highlighting the techniques of viewing and dividing the forms for artistic representation. It discusses the Venus de' Medici and Apollo of the Vatican, emphasizing their superior proportions and artistry. These descriptions reflect on how nature and art combine to enhance human and divine forms in sculpture. |

| Jombert - Method - Page 90 |

|

The text discusses the importance of studying antique sculptures, particularly as models of male deities, for drawing and enhancing artistic skill. It notes that these sculptures, while not perfect imitations of human nature, offer a divine ideal to strive for in art. Specific references are made to sculptures such as Apollo and Antinoüs, describing their representations and significance. |

| Jombert - Method - Page 91 |

|

The text discusses the challenges faced by artists in capturing the noble and beautiful character of faces, especially when creating sculptures or paintings. It notes the rarity of achieving a realistic resemblance, especially in France, attributing this to nature's imperfections. The text also observes that certain beauty characteristics, such as a broad chest, are admired in classical art. |

| Jombert - Method - Page 92 |

|

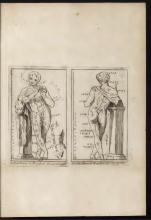

The text describes the discovery of another statue of Antinous and provides detailed descriptions and measurements of various figures from plates 62 to 65. There is a comparison between figures like Venus, Apollo, and Antinous, and a description of the famous Laocoön sculpture from the Vatican. The discussion includes units of measurement used in artistic contexts. |

| Jombert - Method - Page 93 |

|

The text describes a sculpture of two monstrous serpents and involves artists from Rhodes. Michelangelo and Pliny praised its artistic significance, noting its creation from a single marble block and the exceptional anatomical details it portrays. The passage emphasizes the sculpture’s intricate depiction of age, pain, and anatomical accuracy, urging detailed study to appreciate its beauty and articulation. |

| Jombert - Method - Page 94 |

|

The text discusses admiration for the classical figures of Laocoön and his sons, emphasizing their aesthetic perfection. It highlights the Gladiator statue at Borghese Villa by Agazius, noting its ideal representation of human anatomy and movement during a vibrant age. The passage underlines the detail and execution excellence that makes these figures prime subjects for study. |

| Jombert - Method - Page 95 |

|

The text focuses on the study and comparison of a gladiator sculpture, noting its unique stance where one leg appears longer due to tension. Different plates present measurements of the statue in various views, and the analysis emphasizes how the sculpture represents both strength and agility. There's also a description of another figure in a marble group depicting a mother questioning her senator son in the Ludovisia Villa. |

| Jombert - Method - Page 96 |

|

The text discusses the division of a human figure into various parts, highlighting a specific sculpture known as 'The Faun holding Bacchus' from the Plates 70, 71, and 72. It praises the muscular yet delicate nature of the sculpture, focusing on its physical features like thighs and legs. The text also compares this antique sculpture with work by later sculptors such as François du Quesnoy, noting their grace and detail. |

| Jombert - Method - Page 97 |

|

The text discusses the characteristics distinguishing modern sculptures from ancient Greek ones, emphasizing the attractive features of softness, proportion, and contour. It reflects on how modern sculptors have enhanced the art form beyond what was known to the ancients. Additionally, it describes a series of plates depicting a Faun, detailing the measurements and presentation of these sculptures. |

| Jombert - Method - Page 98 |

|

The text discusses the artistry in ancient statues, highlighting the challenge of combining multiple models to achieve perfection. It emphasizes understanding nature to create harmonious figures. Additionally, the text details the structure of specific sculptures, such as the Faun of the Villa Borghese, categorized into sections for detailed study. |

| Jombert - Method - Page 99 |

|

The text describes three historical figures depicted in plates numbered 75, 76, and 77. The first figure, the Dying Gladiator, is noted for its realistic portrayal of bravery in the face of death. The second figure features a marble group with Apollo playing a seven-pipe flute, praised for its proportions and refinement. The third figure, the Hermaphrodite, is celebrated for its ingenious, graceful pose, contrasting with the Venus de' Medici. |

| Jombert - Method - Page 100 |

|

This page analyzes the beauty and technical aspects of an antique satyr figure and an Egyptian figure, emphasizing the importance of studying these forms for refining drawing skills. The satyr is noted for its artistic treatment, while the Egyptian figure highlights a Greek imitation of Egyptian styles. Despite some stiffness due to material challenges, both figures are commended for their detailed and admirable anatomy. |

| Jombert - Method - Page 101 |

|

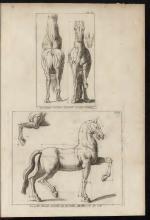

The text describes the proportions and artistic qualities of several classical statues and figures, like "The Nile" and "The Flayed Little Horse". It highlights the beauty and style of these works, emphasizing their grandeur and detail. The passage also references other esteemed antiquities like Venus, the Wrestlers, and the Faun, noted for their anatomical precision and artistic finesse. |

| Jombert - Method - Page 102 |

|

The text discusses the significance of studying antique sculptures to attain perfection in drawing and sculpture. It praises the works like "Walking Diana" and "Torso," highlighting their grace and importance for young artists. The text also contrasts ancient and modern sculpting techniques, emphasizing the aesthetic superiority of ancient methods. |

| Jombert - Method - Page 103 |

|

The text discusses the challenges and limitations of creating genuine beauty in art, emphasizing that the Ancients' ability to produce exquisite architectural ornamentation has not been matched by modern architects. It highlights the preciousness of the artistic relics of Antiquity as eternal models of good taste. It also mentions the unknown details of ancient artists' lives, noting four major schools of painting and sculpture in ancient Greece, with the Isle of Rhodes being particularly notable for preserving its tradition. |

| Jombert - Method - Page 104 |

|

The text discusses ancient sculptures attributed to Rhodian sculptors, as reported by Pliny. It emphasizes the importance of a structured approach in studying art, particularly drawing, for young learners. Key exercises include training the eyes for precision and accustoming the hand to use pencils and pens, stressing the role of practice in acquiring these skills. |

| Jombert - Method - Page 105 |

|

The text emphasizes the importance of learning Geometry and Perspective for young artists, as they are foundational for painting. Geometry is highlighted as essential not only for art but also for architecture and sculpture, while perspective is crucial for accurately representing objects without relying on tools like rulers or compasses. The text suggests beginning the study of these subjects in youth for more effective learning. |

| Jombert - Method - Page 106 |

|

The text discusses the importance of acquiring the habit of copying drawings as a foundational skill in learning to draw. It emphasizes the study of Anatomy and proportions as essential elements in achieving a true representation of forms, especially in human figure drawing. The passage highlights the relationship between Anatomy, which provides structure, and proportions, which contribute beauty, arguing for Anatomy as the starting point in art education, and references a published treatise on perspective for artists. |

| Jombert - Method - Page 107 |

|

The text discusses the importance of understanding proportions in art, originating from nature, and the need to study anatomy and established proportions for creating a perfect figure. It highlights the unique attributes that Antique art brings to the understanding of beauty, grace, and expression. The text suggests that studying Antique figures is crucial for artists to grasp the essence of beauty and accurately represent nature. |

| Jombert - Method - Page 108 |

|

The text discusses the importance of studying drawings and models, using examples like Raphael's approach to combining Antique and natural elements to guide young artists. It emphasizes education on the inherent qualities of art from Antiquity—characterized by simplicity and nobility—while also considering personal interpretation and technical practice. Initial studies are essential for understanding beauty and flaws in models, which leads to a deeper knowledge of nature and art. |

| Jombert - Method - Page 109 |

|

The text discusses the importance of understanding chiaroscuro, the artistic technique of using light and shadow. It emphasizes the necessity of combining contrast, relief, and roundness in figure drawing to create satisfaction in the viewer's eye. Additionally, it suggests drawing from nature and later refining with classical influences. |

| Jombert - Method - Page 110 |

|

The text discusses the effects of light and distance on perceived color and shadow in art, highlighting how objects appear different depending on how far they are from the viewer. It explains that colors change due to the distance light has to travel and the intervening air, noting that colors appear less vibrant in shadows. The document also describes the influence of vapor-filled air on the appearance of shadows at different times of the day. |

| Jombert - Method - Page 111 |

|

The text discusses the relationship between painting and sculpture, focusing on how colors appear based on lighting conditions. It offers general rules for understanding shadows, light, and reflections, emphasizing chiaroscuro effects. It also provides guidance on observing how light and shadows play on different surfaces and in different artistic contexts. |

| Jombert - Method - Page 112 |

|

The text discusses the importance of learning both drawing and modeling for artists. It instructs on painting softly, avoiding harsh outlines to integrate the painting with its atmospheric surroundings. The text emphasizes harmonizing shadows and light in artwork to create unity in tones and colors. |

| Jombert - Method - Page 113 |

|

The text discusses the value of relief drawing and modeling in the artistic development of young painters, suggesting this practice aids the imagination. It notes that many accomplished painters were also skilled in both drawing and sculpting, enhancing their understanding of form and shade. Furthermore, it explains how light and shadow affect the perception of color and form in nature and painting, emphasizing the natural blending of colors and tones without artificial reinforcement. |

| Jombert - Method - Page 114 |

|

This text discusses the relationship between sculpture, painting, and drawing, emphasizing how modern sculptors display precision similar to that of skilled painters. It highlights that both arts, sculpture, and painting, aim to imitate nature but through different methods. It also explores painters' views on the integration of coloring with drawing, noting that those deeply engrossed in drawing may find coloring challenging due to their developed drawing habits. |

| Jombert - Method - Page 115 |

|

The text discusses the importance of early practice in handling brushes and colors for art students, noting that habits form around what is practiced early. It criticizes poor guidance from teachers who lack principles in coloring and suggests that change from bad coloring habits to good ones is rare but possible by painting from nature. It mentions that famous artists like Raphael and Da Vinci never fully mastered good coloring, emphasizing that great colorists emerge from specific schools. |

| Jombert - Method - Page 116 |

|

The text discusses how novice artists often struggle to escape poor practices learned from copying trivial color usages in art. It emphasizes drawing not only for outline accuracy but also for character expression, noting that colors add depth. The importance of expressing variety in line work and understanding nature is highlighted to convey authentic representation in art. |

| Jombert - Method - Page 117 |

|

The text discusses how to approach drawing animals, landscapes, and human figures by respecting their unique characteristics. It explains techniques for rendering nudes with soft, even shadows and draperies with firmer touches using hatching to suggest movement and form. The best methods for drawing these elements, especially on colored paper, involve using white highlights appropriately to create depth and dimension. |

| Jombert - Method - Page 118 |

|

The text discusses the study of drapery in art in addition to the nude. It describes the difficulty in choosing and arranging fabric folds and suggests studying natural fabrics like linen, serge, and wool. Raphael is noted for his use of serge for realistic effect, and practice involves sketching and memorizing fold arrangements. |

| Jombert - Method - Page 119 |

|

The text explains the importance of using full-sized models for achieving realistic proportions and folds in drawing. It also advises on using slightly aged cloth for draperies to create more natural folds and mentions ancient sculptors' techniques. Additionally, the text discusses the variety found in animal coverings like fur or feathers, highlighting nature's diversity. |

| Jombert - Method - Page 120 |

|

The text discusses the characteristics of animals, focusing on their hair or wool, and how these traits can be expressed in drawing. It emphasizes using the pencil or pen to capture these characteristics skillfully, noting that over-detailing can detract from authenticity. It also introduces the study of landscape painting, suggesting different approaches for beginners and those with experience. |

| Jombert - Method - Page 121 |

|

The text discusses the challenges and techniques of drawing trees and foliage in landscapes. It emphasizes understanding the structure and position of branches and leaves, and mentions notable artists like Titian and Carracci for their exemplary techniques. The principles shared aim to guide beginners in achieving a natural and pleasing depiction of trees. |

| Jombert - Method - Page 122 |

|

The text discusses techniques for accurately representing trees in drawing. It emphasizes the importance of observing nature closely and avoiding the mistake of using the same leaf stroke for all tree types. The author also highlights the need to forget previously learned techniques when drawing from nature to achieve precision. |

| Jombert - Method - Page 123 |

|

The text discusses how different trees exhibit varying configurations of branches and leaves, which in turn affects landscape depiction by revealing or obscuring the sky. It emphasizes the importance of accurately replicating nature as it is seen, rather than attempting to alter it for aesthetic purposes. The passage further advises that novice artists will benefit more from studying and copying prints made by master artists rather than directly from paintings. |

| Jombert - Method - Page 124 |

|

The text discusses the importance of imitating the techniques of great artists like Cornelle Cort and Augustin Carraches to learn drawing. It emphasizes observing nature, particularly the appearance of branches and leaves, to develop a better perspective. The text also recommends studying landscapes and artworks by recognized masters such as Titian and the Carraches to refine one's style and technique. |

| Jombert - Method - Page 125 |

|

This text explains the process of learning and refining art, particularly in the study of landscapes and nature. It emphasizes the importance of selecting methods taught by nature and good practices for perfection. Additionally, it describes how 'studies' in art refer to individual parts prepared separately, aiding artists in ensuring accuracy and enhancing their work. |

| Jombert - Method - Page 126 |

|

The text provides insights on how landscape artists should study and replicate the natural effects observed in various elements like trees, skies, and distant views, ensuring variety and specificity in technique. It emphasizes learning the general painting rules as foundational for landscape art and the importance of perspective in creating realistic landscapes. |

| Jombert - Method - Page 127 |

|

The text discusses how leaves closer to the ground are larger and greener because they receive more sap, while those higher up change color earlier. It also touches on the essential elements in landscape paintings, emphasizing the importance of capturing the general forms and lights and shadows. It warns against a superficial study method that can lead to a style disconnected from nature. |

| Jombert - Method - Page 128 |

|

The text discusses the errors artists make when adding elements to a drawing that weren't actually present, misunderstanding natural light effects. It emphasizes drawing from nature with accuracy to capture true forms, light, and shadow. Concluding on the importance of finishing studies on site, it warns against completing them elsewhere to avoid inaccuracies. |

| Jombert - Method - Page 129 |

|

The text provides guidelines for drawing plants and flowers, emphasizing their delicacy and variety. It advises practicing with diligence to excel in drawing, particularly for those pursuing painting professionally. For hobbyists, it suggests a more relaxed approach and promises to offer various creative methods in the subsequent chapter. |

| Jombert - Method - Page 130 |

|

Chapter Seven discusses various methods for copying a drawing or painting, especially useful for those not skilled enough to copy by sight. One highlighted method is tracing, which involves darkening the back of the drawing or using a thin sheet to avoid damaging the original. The process includes using black pencil powder, a cloth, and securing the work with pins. |

| Jombert - Method - Page 131 |

|

This text describes techniques for drawing and copying designs onto paper. It outlines a method using a blunt needle to transfer designs by tracing on darkened paper and discusses refining the drawing with pencil or pen. Another technique called pouncing involves transferring drawings using a fabric pad filled with charcoal or other powders. |

| Jombert - Method - Page 132 |

|

The text describes techniques for transferring drawings by perforating the original and using pumice dust to mark the outlines. It explains how the method can be used repeatedly and highlights benefits in painting and embroidery. Additionally, it offers a method for drawing from life using thin paper to see and transfer outlines. |

| Jombert - Method - Page 133 |

|

The text explains a technique for copying and tracing drawings by fixing two sheets of paper together, using the daylight or a candle behind a transparent surface to see through the original. This allows for the outline to be traced on white paper with charcoal or graphite without damaging the original drawing. This method is used by engravers as well, although often they use simpler methods if the original is not significant. |

| Jombert - Method - Page 134 |

|

The text explains a method for transferring a drawing onto glass using a transparent medium and a sanguine pencil. It involves applying gum arabic or egg white to the glass surface and using moist paper to capture the drawing. The process includes reversing the image, which might require copying it again to restore the original orientation. |

| Jombert - Method - Page 135 |

|

The text describes a technique called "capturing with a veil" used for copying large paintings without damaging the original. It involves using a fine silk veil stretched on a frame, through which the painting is visible. Artists trace the lines with a special chalk, then transfer them to another surface, all while ensuring no harm is done to the original artwork. |

| Jombert - Method - Page 136 |

|

The text provides instructions on how to transfer a drawing onto a canvas using a veil and crêpe. It emphasizes the importance of securing the drawing to avoid errors and explains the process of gently applying pressure with soft paper to transfer the pencil marks. Finally, it advises on refining the drawing with chalk and offers cautions about shaking the canvas to avoid disturbing the chalk. |

| Jombert - Method - Page 137 |

|

The text describes methods for copying and reducing the size of drawings. It mentions the use of crêpe to transfer images by adhering chalk, and introduces 'graticuler' or 'craticuler', a grid method for resizing artworks. The approach involves dividing the original artwork into a grid for accurate reproduction. |

| Jombert - Method - Page 138 |

|

The text describes methods for copying a drawing onto canvas or paper by dividing the surface into a grid of equal parts. It explains the use of a technique called "tringler" or "fingler," which involves marking lines with a chalked string instead of using a ruler and pencil. The importance of practice in drawing is highlighted for successfully mapping objects from the original to the copy. |

| Jombert - Method - Page 139 |

|

The text describes a method of drawing a portrait using a grid system on canvas. A painter uses a grid frame to proportionally transfer the features of a face onto a canvas. By using this technique, the painter ensures accurate proportions and finishes the portrait without concerning himself with exact likeness initially. |

| Jombert - Method - Page 140 |

|

The text describes a method of achieving precise and successful drawings, particularly portraits. It explains techniques for copying large paintings by using a frame to aid in creating proportional copies. Additionally, it details using oiled or varnished paper to trace drawings for reproduction onto white paper. |

| Jombert - Method - Page 141 |

|

The text provides techniques for copying drawings, such as using lacquer and tracing paper or using a mathematical compass for resizing. It describes how to prepare and use these tools effectively for those unfamiliar with drawing. Additionally, inventions like measurement tools are recommended for easier copying of images. |

| Jombert - Method - Page 142 |

|

The text discusses a drawing tool used for copying and enlarging drawings, known as the Pantograph or Monkey. Despite its flaws, changes have been made to simplify it and improve accuracy, validated by the Academy of Sciences. The tool, described in a separate booklet, is successful among artists. |

| Jombert - Method - Page 143 |

|

The text discusses a simple and efficient instrument designed by Mr. Buchotte, useful for scaling drawings. It refers readers to a detailed book with related information and highlights the usefulness of such tools for those unfamiliar with drawing, sold by specific booksellers in Paris. The text ends with a mention of a mathematical compass included in a new edition. |

| Jombert - Method - Page 144 |

|

This chapter explains the use of the Camera Obscura in drawing, emphasizing its ease of application and enjoyment. It discusses the initial plan to let readers explore using the camera but acknowledges the challenges in its mechanical construction, requiring experimentation. The chapter aims to spare readers the effort by describing two machines intended as practical and pleasant. |

| Jombert - Method - Page 145 |

|

The text discusses the relative merits of two machines used in art, noting that the first is more stable and easier to use while the second is simpler and more portable. It highlights the advantages these machines offer to artists, particularly in accurately rendering the size and perspective of objects. The use of these machines, and their consistent viewpoint, aids in bringing together multiple objects in a single painting, with a note on the historical use of the camera obscura by Flemish painters. |

| Jombert - Method - Page 146 |

|

The text discusses how artists have studied and imitated the effects of chiaroscuro to understand light and shadow in art. It warns against too exact imitations as they differ from natural vision, using the concept of a camera obscura as an example. Additionally, it suggests that painters should capture nature truthfully rather than with exaggerated effects. |

| Jombert - Method - Page 147 |

|

The text explains how the camera obscura can accurately represent objects by using a small opening with a convex glass that inverts the image. It describes how light rays passing through the glass provide true representations of objects on a plane. It also notes that mirrors reflecting these rays do not distort the representation. |

| Jombert - Method - Page 148 |

|

The text describes the construction and functionality of an early 'camera obscura,' shaped like a sedan chair, used as a visual aid. It elucidates how the internal table can be adjusted for easy access and illustrates the air-system preventing light penetration. Furthermore, it details components allowing parts of the device to move, enhancing operational flexibility. |

| Jombert - Method - Page 149 |

|

The text describes detailed instructions for assembling parts of a machine used in art or technical drawing. It involves the arrangement and attachment of boards, a box, and a mirror with specific measurements and positioning to ensure functionality. The components include sliding boards, a cylinder with a screw, and a strategically placed mirror, outlining specific angles and setups. |

| Jombert - Method - Page 150 |

|

The text describes the mechanical setup and adjustments for placing and manipulating mirrors and rails in an apparatus for drawing. It details the movement and positioning of parts such as mirrors and how they can be tilted and adjusted vertically and horizontally. A note at the end suggests using bellows to maintain air flow in the machine. |

| Jombert - Method - Page 151 |

|

The text describes how to use a machine to represent objects naturally, involving a setup with paper, a frame, and mirrors. It details the adjustment of a convex lens and mirror angles to project an image of the object onto the paper. The process is explained for both perpendicular and inclined tables. |

| Jombert - Method - Page 152 |

|

This text describes techniques for setting up optical devices to assist in drawing, particularly the use of mirrors and boxes to reflect and capture perspectives. Instructions include positioning mirrors to capture images from balconies or ceiling representations. Additionally, it covers how to manipulate the angles of mirrors for effective reflection onto a drawing surface. |

| Jombert - Method - Page 153 |

|

The text provides instructions on using mirrors to determine angles for inclined and parallel paintings. It includes specific instructions for positioning mirrors to achieve precise angles relative to the horizon. The method is applicable for various angles, relying on a detailed understanding of reflection and inclination. |

| Jombert - Method - Page 154 |

|

The text describes a method using the camera obscura to represent objects from nature or surrounding areas in art. The technique involves positioning the back of the machine toward the sun to achieve clearer reflections of objects. It details the use of mirrors to represent objects from different angles while explaining how light reflection impacts the visual clarity of the representation. |

| Jombert - Method - Page 155 |

|

This section describes how to copy paintings or prints using the camera obscura. It explains the positioning and adjustments needed for the board and convex glass to achieve accurate or altered sizes of engravings. The process involves manipulating the distance and orientation of the board and engravings in relation to the sun and the device. |

| Jombert - Method - Page 156 |

|

The text discusses the method of representing portraits using a machine, likely a camera obscura. It describes the challenges of capturing the likeness of a person precisely, especially when representing the head at its natural size. The use of lenses and the exact positioning required to accurately capture features are emphasized. |

| Jombert - Method - Page 157 |

|

The text discusses the importance of carefully determining the opening of a convex glass lens in drawing. It suggests that the lens should typically be set as one would for telescopic lenses, adjusting for lighting conditions to achieve better line definition. It highlights the balance between preventing excess light reduction while maintaining precision in depicting objects. |

| Jombert - Method - Page 158 |

|

The page describes the necessity of having thin, round sheets of metal, like tin or copper, with various openings to work with glass. It details a machine resembling a box, illustrating its dimensions, structure, and the mechanism of how glass or paper is positioned and used with it. Additional features of the machine, such as slats for supporting a painted canvas, are also explained. |

| Jombert - Method - Page 159 |

|

The text describes components and adjustments of a drawing machine, notably how the box is supported by wooden pieces and secured with iron pegs. It explains adjusting the box's position, including tilting mechanisms and attaching a mirror using a sliding ruler. The machine's transportability is highlighted, alongside securing methods to prevent sliding and incorporating elements like a small turret and painted canvas. |

| Jombert - Method - Page 160 |

|

The text provides instructions for using a drawing machine, describing how to set up and adjust the device to properly depict objects. It explains the method to properly use a secondary machine in drawing, including adjusting angles for optimal perspective. Observations are given on improving the invention and maintaining accurate perspectives. |

| Jombert - Method - Page 161 |

|

The text discusses the use and construction of a portable camera obscura. It highlights the importance of using polished mirrors and the challenges of mirror placement due to humidity. The description includes details on building a box with a curtain and placing lenses for viewing, ensuring minimal light intrusion. |

| Jombert - Method - Page 162 |

|

This text describes a drawing device using a flat mirror suspended by pivots, which allows the artist to project and trace images. The device involves adjusting the mirror's angle to reflect objects clearly onto paper placed at the bottom of a box. It details how to secure the mirror and explains the use of vellum and different tools for tracing. The method is best suited for small-scale portraits due to inherent difficulties in larger formats. |

| Jombert - Method - Page 163 |

|

The text provides instructions for creating a portable drawing device resembling a large book, using hinges and hooks for easy folding and transport. It also mentions ensuring proper lighting for objects to appear better on paper. A decorative emblem at the bottom suggests the end of this section. |

| Jombert - Method - Page 164 |

|

The text contains labels for figures illustrating methods and tools related to drawing. These tools are likely aids for learning to draw with precision, consistent with the context of Jombert's book on drawing techniques. |

| Jombert - Method - Page 165 |

|

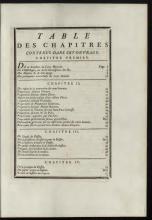

The table of contents outlines chapters on the structure and proportions of the human body, drawing techniques, and observations on artistic practices. It includes references to classical principles by Vitruvius and artists like Albert Durer. Chapters also cover practical methods for studying drawing and specific techniques like drawing with a pencil. |

| Jombert - Method - Page 166 |

|

The text is a table of contents that provides page numbers and themes for sections on drawing techniques and descriptions of famous statues in Rome and Italy. It includes topics on sketching, shading, using different tools, and studying classical statues. The document also outlines the necessity of understanding geometry, anatomy, and chiaroscuro in drawing. |

| Jombert - Method - Page 167 |

|

The page is from the table of contents of a book on drawing and features chapters focusing on different techniques and methods for art, including landscape studies, copying illustrations, and using the Camera Obscura. Chapter VII discusses various ways to replicate artwork, while Chapter VIII covers the use of a Camera Obscura. An approval note for the manuscript is included at the bottom, highlighting its usefulness to the public. |

| Jombert - Method - Page 168 |

|

This document is a privilege granted by King Louis of France, allowing Charles-Antoine Jombert to print and distribute various literary and artistic works. It specifies the works included, the nine-year privilege duration, and the prohibition of unauthorized reproductions. Violators face penalties, including fines and confiscations, with provisions for library registrations. |

| Jombert - Method - Page 169 |

|

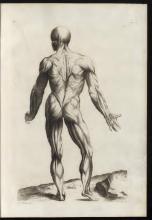

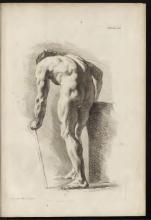

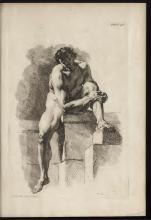

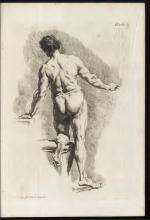

The image provides an anatomical drawing labeled as 'Plate 1.' It features a human skeleton, likely used for educational purposes in understanding human anatomy for drawing. |

| Jombert - Method - Page 170 |

|

This page, labeled as Plate 2 by Titian, features the artistic work of Titian. The text is a simple acknowledgment of the artist's contribution to the illustration. |

| Jombert - Method - Page 171 |

|

The image contains an anatomical illustration labeled as Plate 4, engraved by Pollich and drawn from Albinius. It is part of a collection meant to aid artists in learning about human anatomy. |

| Jombert - Method - Page 172 |

|

|

| Jombert - Method - Page 173 |

|

The text indicates that the drawing was done by Titian. It is an anatomical study and part of Charles-Antoine Jombert's 1784 book on drawing. The focus is on illustrating human musculature. |

| Jombert - Method - Page 174 |

|

The image includes a title, "Plate," and indicates a reference to a star, as well as the term "Making N. Clear." It seems to be one of many educational plates from a drawing book, focusing on human anatomy. |

| Jombert - Method - Page 175 |

|

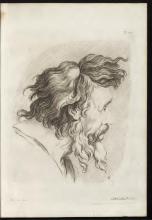

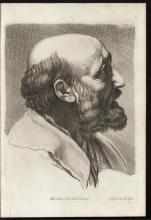

This page from the book shows various sketches of a human head from different angles. Each position is labeled to guide the drawing process. The focus is on illustrating head proportions for artistic purposes. |

| Jombert - Method - Page 176 |

|

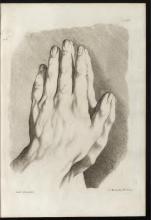

The page contains annotations identifying three illustrations: Figure 1st, likely a hand, and Figures 2 and 3, both feet. It is labeled as Plate 9, suggesting these are part of a series. The illustrations aim to aid in understanding the anatomy for drawing purposes. |

| Jombert - Method - Page 177 |

|

The image has sketches of six different eyes, with artist credits below. It illustrates detailed studies for understanding human expression, showing work by Le Brun and Denisot. This page is likely a part of a broader educational resource on drawing. |

| Jombert - Method - Page 178 |

|

The text indicates plate number 12 and attributes the artwork to Brun. It appears to be a sketch of human eyes with the term 'Ranaches' present, which might refer to a title or name. The text provides an attribution but lacks further descriptors. |

| Jombert - Method - Page 179 |

|

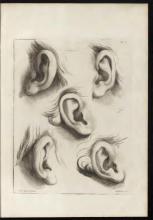

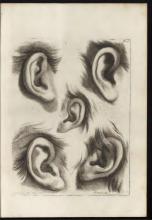

This page features detailed illustrations of human ears to aid in understanding their structure. The sketches are labeled as 'Plate 18' and are created by the artist Cochin. The image serves as a learning tool for artists studying human anatomy. |

| Jombert - Method - Page 180 |

|

The page includes annotations for Plate 13, crediting artists known for drawing portraits. The text suggests the drawings are based on works by these artists, possibly for educational purposes in learning to draw human anatomy, specifically the ear. |

| Jombert - Method - Page 181 |

|

Plate 24 features a drawing by Vien after an ancient model. The text indicates it is inspired by classical art, suggesting a study in classical proportions and techniques. |

| Jombert - Method - Page 182 |

|

This page features an illustration titled 'Plate 18,' drawn by Jean, inspired by Raphael, and engraved by Bertrand. It is part of a series representing detailed studies of human anatomy for artistic instructional purposes. The focus is on replicating the styles and techniques of renowned artists. |

| Jombert - Method - Page 183 |

|

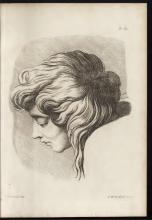

The text includes credits for the drawing and engraving of a detailed human facial study. It attributes the drawing to Vien, inspired by Raphael, and engraved by Reclusit. This is marked as Plate 16. |

| Jombert - Method - Page 184 |

|

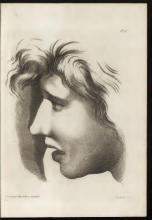

This is Plate 17 from the book, drawn by C.P. Marillier of the Imperial Academy and engraved by Redouté. It features a detailed study of a human face in profile, focusing on anatomy and artistic technique. |

| Jombert - Method - Page 185 |

|

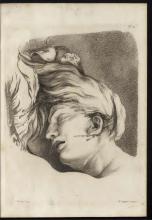

The image includes a drawing labeled as being created by Raphael, identified as Figure 28. It reflects an artistic study typical of the instructional art book context. The drawing is a finely detailed side profile of a face. |

| Jombert - Method - Page 186 |

|

The text identifies the image as Plate 19, with inspiration from Raphael. It credits C. N. Cochin with the drawing and engraving. The terms used indicate historical art terminology, specifying the creators of the piece. |

| Jombert - Method - Page 187 |

|

The image contains the label 'Plate 20,' indicating it is the twentieth illustration in the series. It is part of a collection of artistic studies published in a book about learning to draw the human figure. |

| Jombert - Method - Page 188 |

|

|

| Jombert - Method - Page 189 |

|

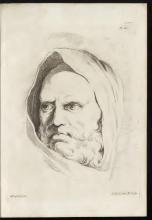

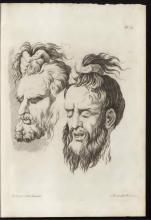

The image consists of Plate 22 from an art book, with a drawing by Raphael and engraving by C.N. Cochin. This page features a detailed engraving of a man’s head, part of a collection aimed at teaching drawing techniques. |

| Jombert - Method - Page 190 |

|

The text includes identifiers for a plate number along with the attribution of artwork. Raphael is acknowledged as the painter, and Cochin is noted as the engraver. These are typical notations for artworks reproduced in historic books for educational purposes. |

| Jombert - Method - Page 191 |

|

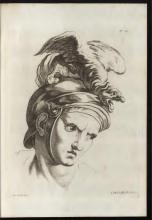

The engraving titled "Plate 24" is based on a painting by Raphael and engraved by C.N. Cochin. It showcases a man's head with classical features, contributing to art studies of anatomy and expression. |

| Jombert - Method - Page 192 |

|

The text identifies the image as Plate 25, attributed to a painting by Raphael. The engraving was done by C.N. Cochin the Elder. |

| Jombert - Method - Page 193 |

|

The text identifies the artist as C.N. Cochin, who sculpted the piece. The image complements the textual content and serves as an instructional example for learning drawing techniques. |